It’s not like miracles happen: IndyCar told to work hard in Mexico City for a race in 2026 instead of World Cup nonsense on the same day causes global outrage

MEXICO CITY – The roar of high-speed engines at Autódromo Hermanos Rodríguez has long been a dream deferred for the NTT IndyCar Series, but recent developments have turned that dream into a rallying cry for persistence amid what many are calling a “World Cup nonsense” fiasco. On October 25, 2025, just two days shy of the current date, Mexico City’s premier motorsport promoter, Ricardo Escotto, delivered a blunt message to IndyCar officials: “It’s not like miracles happen.” Escotto urged the series to “toil” and build a solid foundation now if they want a race in 2027, rather than chasing unrealistic slots around the FIFA World Cup’s sprawling 2026 schedule. His words, delivered during a press briefing at the iconic track, have ignited a firestorm of global outrage, with fans, drivers, and industry insiders decrying the soccer tournament’s overreach as a suffocating force on international sports calendars.

The controversy stems from IndyCar’s abrupt announcement on September 13, 2025, that it would not add a Mexico City race to its 2026 calendar – a decision pinned squarely on the “significant impact” of the FIFA World Cup. The tournament, co-hosted by the United States, Canada, and Mexico from June 11 to July 19, 2026, will transform Estadio Azteca – located mere kilometers from the Autódromo – into a soccer mecca. As the venue for the opening match on June 11 and several group-stage and knockout games through early July, the Azteca’s preparations and the ensuing fan frenzy are expected to paralyze Mexico City’s logistics. For IndyCar, which had been negotiating for over a year with Escotto’s team and venue operators, the clash meant no viable summer window: May was booked, spring dates scrapped by the track, and post-July slots jammed with existing races like Laguna Seca and Portland.

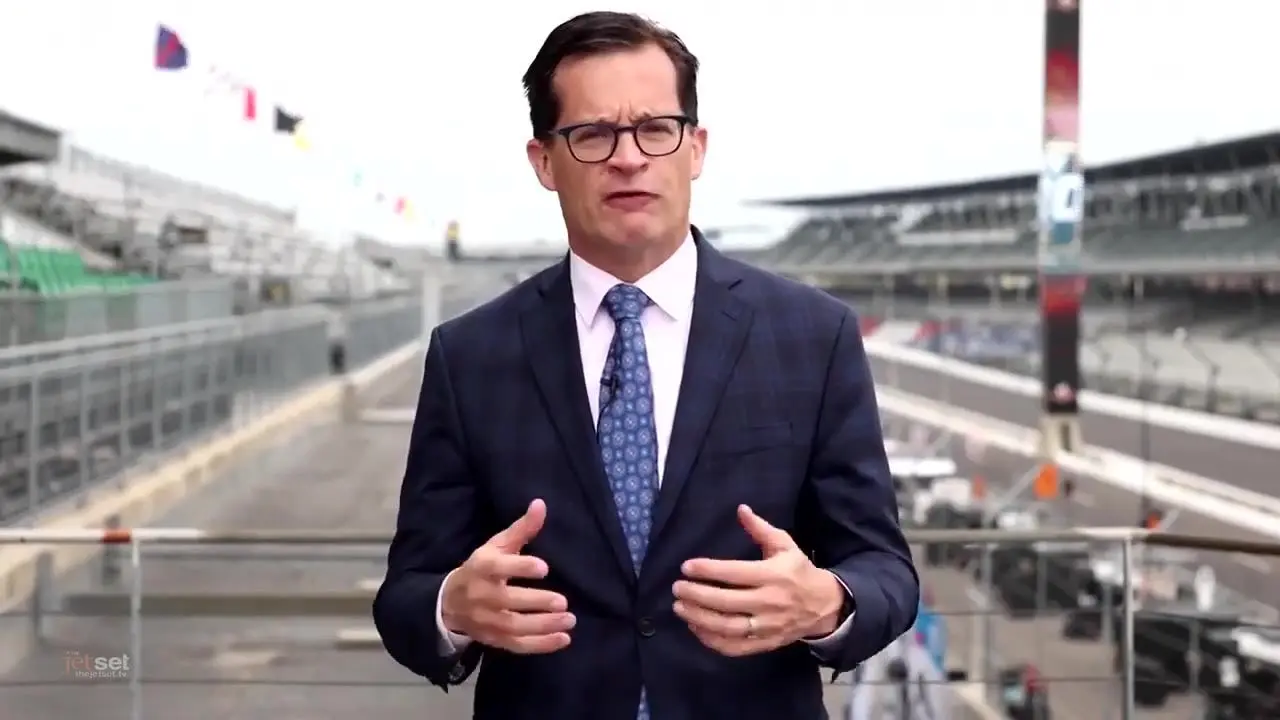

Penske Entertainment Corp. President and CEO Mark Miles, in a statement that now feels like a prelude to the backlash, expressed measured disappointment. “While extensive progress was made alongside the venue’s operating group and our potential promoter, ultimately the significant impact of next year’s World Cup proved too challenging to ensure a successful event, given the available summer dates,” Miles said. He emphasized the series’ commitment, adding, “We will keep working to bring our racing to Mexico and hope for an event to be on the schedule as soon as the right opportunity presents itself.” Yet, to many, this sounded like corporate doublespeak – a polite way of admitting defeat to FIFA’s behemoth.

No one felt the sting more acutely than Pato O’Ward, the Monterrey-born Arrow McLaren driver who has been IndyCar’s most vocal champion for a home race. O’Ward, who won the 2025 Indianapolis 500 in dramatic fashion, issued a heartfelt response to the September news: “No one wants a race in Mexico more than me. But we want to create an incredible event that is built to last. That requires the right date and the right year for fans and sponsors to fully get behind our sport.” His words, laced with optimism, now ring hollow against Escotto’s pragmatic rebuke. O’Ward, speaking to reporters after a recent test session in Texas, admitted the emotional toll: “It’s frustrating because we’ve seen the passion here – the crowds for F1, the buzz from NASCAR’s debut. But Ricardo’s right; miracles don’t just happen. We need to grind.”

Escotto’s October 25 comments, made during a review of the track’s 2025 season that included Formula 1’s Mexican Grand Prix and Formula E’s ePrix, pulled no punches. As managing director for OCESA, the promoter behind NASCAR’s successful Viva Mexico 250 in June 2025, Escotto highlighted the World Cup’s role in derailing not just IndyCar but also NASCAR’s return. “Next year, there were some scheduling problems and it was difficult, and the World Cup in the middle didn’t facilitate certain things,” he said. “But I think IndyCar and NASCAR have great potential to grow in Mexico and take advantage of this wonderful fanbase, so we should expect news on that for 2027.” He likened the effort to constructing a durable bridge rather than a hasty scaffold, insisting that series like IndyCar must invest in local partnerships, sponsor outreach, and infrastructure tweaks to avoid competing with soccer’s gravitational pull.

The global outrage erupted almost immediately on social media and in sports forums, with hashtags like #WorldCupNonsense and #SaveMexicoIndyCar trending worldwide. Fans in Mexico, where open-wheel racing holds nostalgic ties to the Champ Car era of the early 2000s, flooded platforms with memes depicting FIFA President Gianni Infantino as a soccer ball eclipsing a checkered flag. “This isn’t hosting; it’s monopolizing,” tweeted one Mexico City resident, echoing a sentiment shared by over 50,000 users in the first 24 hours. American enthusiasts, many of whom followed O’Ward’s rise, decried the decision as shortsighted, pointing to IndyCar’s recent expansions like the 2026 Grand Prix of Arlington around AT&T Stadium as proof of its momentum. Even in Europe, where Formula 1’s Mexican GP draws massive crowds, outlets like Autosport labeled the conflict “a scheduling farce that prioritizes one sport over the global calendar.”

Critics argue the World Cup’s unprecedented scale – 48 teams across 16 venues, including 13 matches in Mexico – has created a ripple effect that’s choking other disciplines. In Mexico City alone, the tournament’s demands on transportation, security, and hospitality resources make concurrent events untenable. Yet, some see silver linings: Formula E’s January 10, 2026, ePrix and F1’s November Grand Prix proceed unaffected, slotted outside the soccer window. NASCAR, fresh off its 2025 debut that drew 75,000 spectators, echoed Escotto’s call for long-term planning, with series officials hinting at a joint motorsport festival in 2027.

As IndyCar finalizes its 2026 schedule – still pending release but rumored to include revamps like a Markham, Ontario, street race – the Mexico saga underscores broader tensions in the sports world. The series, buoyed by record TV ratings and O’Ward’s star power, stands at a crossroads. Will it heed Escotto’s advice and invest in Mexico’s “wonderful fanbase,” perhaps through exhibition events or driver appearances during the World Cup? Or will the outrage fizzle into another missed opportunity, like the abandoned Champ Car races of yesteryear?

For O’Ward and his compatriots, the fight is personal. “I’m motivated to carry this effort forward and take part in a future race in my home country,” he vowed. In a city where the Azteca’s echoes of 1970 and 1986 World Cups still resonate, IndyCar’s return could blend soccer’s fervor with racing’s adrenaline. But as Escotto warned, it won’t come easy. Miracles, after all, are for storybooks – in the real world, champions build their legacies lap by lap.